3D printers pave the way for creative innovation among students

The emergence of 3D printing has reshaped many industries, from manufacturing and construction to automotive and aerospace. What was previously seen as a novelty or niche solution by some has become a maturing technology, shifting from “rapid prototyping” to “additive manufacturing.”

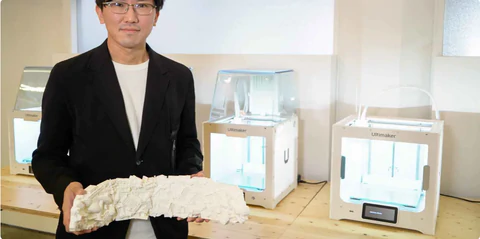

Toshiki Hirano, Director and Project Assistant Professor at Sekisui House – Kuma Lab, University of Tokyo

T-BOX: How it all started

The T-BOX project was established in June 2020 by the architect Kengo Kuma as a workshop with various machines for digital fabrication, mainly for the purpose of studying the relationship between digital technology and architecture.

“T-BOX means many different things to us”, Hirano says about the project name. “’T’ refers to Tokyo from The University of Tokyo, technology, and toolbox. Since then we have looked at T-BOX as a ‘tool box’ with various digital fabrication equipment.”

A facility that breeds creative talents

The University of Tokyo is researching the future of architecture using technology, while Sekisui House – which provided a donation to start the project – is exploring the “the future of living”. The main purpose of the collaboration is that these mutual and complementary capabilities will help in the development of future talent at T-BOX.

In the past, the department of architecture did not have a production facility with digital fabrication tools. Students had no choice but to purchase their own 3D printers or make their models by hand, which is the conventional method. Now with T-BOX, architecture students can easily create their prototype and use them for presentation purposes.

“I believe that this facility will help students to improve their craft and explore other avenues for growth, such as learning about manufacturing or digital fabrication,” says Hirano. “The fact is, T-BOX is not only exclusive to architecture students. Anyone can visit the facility and use our Ultimaker 3D printers. Everyone is welcome. T-BOX will operate as a facility that breeds creative talents so they are better equipped for the future.”

Inside T-BOX: A closer look

Currently, T-BOX has six Ultimaker 3D printers. Since there is no other facility on the campus that has multiple 3D printers in one lab, Hirano believes that this will be a crucial facility for designers.

On why they chose Ultimaker, Hirano comments: “With digital fabrication growing in popularity, I visited similar facilities overseas. I went to the American University of Architecture and saw that they were using Ultimaker 3D printers. Most students are familiar with the quality of products Ultimaker produces and they often say it’s easy to use.”

“Ultimaker is a good choice because it can handle various filaments, as well as excellent printing accuracy, speed, and high responsiveness. You can start printing your concepts as soon as you enter the data. This allows you to create your work intuitively even without prior technical knowledge. In addition, when advanced adjustments are necessary, you can easily manipulate the parameters to meet your requirements,” he adds.

When we ask him about the adoption of 3D printing in architecture over the last ten years, Hirano admits: “To be honest, I wouldn’t use a 3D printer unless there is a need for me to use one. As we become more digitalised than ever, 3D printers like the ones Ultimaker built have grown in importance in many industries across the globe. Definitely, 3D printing has become a part of the design cycle for architects and students.”

Toshiki Hirano displays one of his 3D printed architectural models

Unbound by restrictions

Currently, the T-BOX lab is using white PLA material, but Hirano and his students are already looking into the possibilities opened up by the wide range of both Ultimaker and third-party filaments they can now leverage. “In the case of ABS material, we are thinking of using various materials to print joints of a building structure in one-third size and actually use it. Essentially, we want to challenge ourselves by using a variety of materials for many different purposes,” Hirano says.

Of course, model-making has always been part of the architect’s process. Students used to make models by hand using styrene boards, for example. But then, you are limited to simple shapes. “Our aim is to break free from conventional norms that limit ideas,” Hirano says. “We want to innovate designs by using 3D printers, having the freedom to translate ideas into actual products. We don’t want to be bound by the complexity of shapes.”

“A 3D printer is not just a tool for making models; it is also a tool that allows you to think freely about architecture and design.”

Digital fabrication facilities

In addition to 3D printers, the digital fabrication equipment found at T-BOX includes laser cutters and CNC processing machines as it aims to combine all resources, technologies and methods to create something meaningful.

Hirano reports that many digital fabrication facilities have a hard time educating students on how to use the equipment. “At T-BOX, we want students to use it freely and voluntarily as much as possible. We have set minimum safety and usage guidelines, but we want them to be able to use the machine without relying on our staff. We want students to explore the capabilities, but we’ll be here to answer any questions. All they have to do is make a reservation online and go from there.”

It’s an example of best practice that’s been getting attention in the architecture, education, and additive manufacturing worlds. On seeing the T-BOX use case, Jürgen von Hollen, Ultimaker CEO, commented: “It is great to see advanced educational institutions like the University of Tokyo recognize the importance of 3D printing and to bring out the full creative inspiration of its students to prepare them to be as impactful as they can be when they enter the professional world.”

What T-BOX has printed

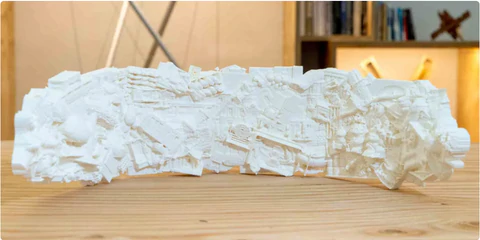

One especially eye-catching print to come out of T-BOX is a 1/10 size 3D printed model of an installation work exhibited at the Design Biennale exhibition in London in 2021. This work is divided into 6 parts, which are printed individually and combined together. The work shows the 3D scanning of various objects in the cities of Tokyo and London and converted them into 3D data.

For example, Maneki Neko, Kaminarimon, Cicadas, Vending Machines, Taiyaki, Donuts, and other objects from Tokyo. In London, various urban elements such as London underground seats, mailboxes, and pubs were 3D scanned, collected, and combined.

In the actual work, a Styrofoam block is carved out with CNC and used as a mold to attach Japanese paper. Finally, the work was transported to London and put up for the exhibition.

“I thought that this work would be quite difficult to print due to the complicated shape scanned using 3D. I printed it with Ultimaker, so even though it has fine details, it printed beautifully and intricately.”

1/10 size 3D printed model of the London Biennale exhibit

University of Tokyo lab with Ultimaker 2+ Connect and Ultimaker S3 printers

Forward to the Future

Towards the end of our conversation with Hirano, we asked him about the future for T-BOX, starting with who else he thinks could benefit.

“I believe that T-BOX will benefit everyone, no matter what their course is. But I believe that graduate school students who need to reinforce concrete formwork may find this facility very useful. Also, students can design a mold with complicated shapes and try to downsize them. This can also be used to design and make small furniture and accessories. The possibilities are endless.”

If budget and space are not issues, I would like to add a few things.

And as for what other tools could be added, Hirano plans to add a few things if budget and space are not issues. “A robot arm and a larger 3D printer that can handle bigger projects. But for now, what we have is more than enough. I feel that I have finally been able to bring global-standard digital fabrication devices to our University, helping students and faculty members go beyond what’s conventional.”

“What’s next for me is I will use our existing 3D printers to educate the entire department of architecture on the value of digital fabrication as they innovate their work. I would like to continue exploring new ways or methods of using Ultimaker products and help encourage students to do the same.”

Toshiki Hirano in the T-BOX lab at the University of Tokyo